No watermaker? No problem…

As young cruisers, we often don’t have the option of buying a water for a long trip or ocean crossing. It wasn’t that that long ago, sailors crossing the ocean had to take or capture all the water they would need on their trip. And cruisers used to find and treat or capture all their water for months, years, on end. This article explores the pros and cons and relative costs of making water ‘the hard way.’

The costs have been normalized to 10 000 gallons of water production to show the relative cost of each system over multiple years of operation. The costs are based on average prices for 2017.

Water consumption

Arguably the most important factor when considering making water is water consumption. The human body requires, on average, about a 1/2 quart of water per day to survive and about a 1/2 gallon to avoid the pangs of thirst. These numbers of course depend on level of exertion and the surrounding environment. In extreme circumstances, the human body can sweat 1 liter (1 quart) of water an hour.

While it is difficult to change the amount of water a body needs, it is quite possible to reduce the amount of domestic water consumption. Helpful strategies for reducing domestic water usage are:

- washing dishes in seawater

- reusing the fresh water rinse from clothes and dishes

- taking navy showers

- cooking one pot meals using easy to clean Teflon pans

- cleaning with a spray bottle

- carrying canned food as opposed to dehydrated supplies

- installing foot pumps instead of automatic electric pumps

When we are being especially miserly, we use approximately 50 gallons per week, which includes one shower from a 3 gallon solar shower bag. If we cruise for half the year, that puts our usage at 1300 gallons per year. To find out what each system would cost for us per year, I would use the following formula:

yearly cost = cost x 1300/10000

Near People

Wherever people live you can be assured that they have a supply of water. It may be potable and it may not be.

Most regions outside of developed countries also have ways of acquiring potable water without needing a watermaker. Throughout Mexico we topped-up our tanks with 5 gallon jugs that were filled with water from a water purification or desalination plant in the local area. The jugs are heavy and cost about $1-2 USD to fill, in addition to the $40 USD for their initial purchase. In one location we had to walk or hitchhike 10 miles to fill up two jugs every second day. They also take up a lot of room on the boat, empty or full. Cost: $2160-4320 / 10 000 gallons

In many cases it is simply easier to use the fresh water that is immediately available and treat it yourself. The four most common methods for treating water are: filtering, chemical treatment, UV treatment and boiling.

Filtration

There are a variety of inexpensive, off-the-shelf, filtration systems for making water potable. We installed an in-line strainer to filter out particulates before it reaches the electric pump. We have a separate tap for pure water that runs from the pump through an under-the-sink, charcoal activated ceramic filter that filters down to 0.3 microns (though 0.1 microns would be better). Because we only use the ceramic filter for drinking water, it doesn’t need to be changed as often as if we were passing all our domestic water through it. It is important when choosing a filter that it is certified by a national/international agency to remove cryptosporidium and cysts and is often paired. Cost: $370-420 / 10 000 gallons

Chemical Treatment

Iodine tablets are a common mainstay in hiker’s and traveler’s backpacks to purify water of unknown quality. Easier even then iodine is unscented household bleach. The CDC recommends adding 1/8 teaspoon (about 8 drops) to one gallon of clear water, or 1/4 teaspoon (16 drops) to a gallon of muddy water to kill most harmful pathogens (not cryptosporidium). When we fill our water tanks we often add bleach as an extra treatment measure. There is a slight taste of chlorine but once it has run through the activated charcoal filter it is barely noticeable. Cost: $5.40-9.00 / 10 000 gallons

UV treatment

Ultra-violet light purification is an increasingly popular way for making water potable. The systems tend to be more expensive than simpler filtration methods. The biggest advantage with a UV system is that it is effective in treating small microbes such as giardia and cryptosporidium. It is often paired with an in-line (0.3-0.5 micron) filter to improve the water quality. Costs $395-595 / 10 000 gallons.

Boiling

The CDC recognizes boiling water for 1-3 minutes as the most effective means for eradicating bacteria and viruses from a water supply. It’s not always convenient if you want a nice cool glass of water, but with a little foresight you can prepare a day’s water the night before and allow it to cool overnight. Cost: $1340-3000 (depending on cost of propane) / 10 000 gallons

When you are on the open ocean you won’t have access to a regular fresh water source. As Coleridge wrote of the ocean ‘water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink.’ Even if you have a high-output RO system on board it is a good idea to think about strategies for acquiring water at sea. The water maker might stop working or the storage tank might become fouled. When you’re at sea you have only two choices for water; capture it or make it.

OCean sailing without a Watermaker

Capturing Water

There are many methods for capturing rainwater and many are specific to the type of boat in which they are used. The more common methods are using the sails, erecting a tarp or other fabric, or damming features of the deck and cabin top.

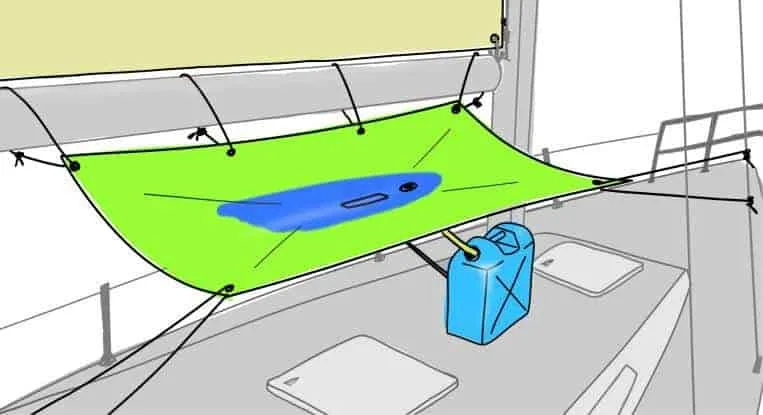

Rainwater harvesting can be surprisingly efficient. Capturing the rain in a 6ft X 6ft tarp from a large rain cloud that drops an inch of rain on its surface would provide more than 23 gallons of water. A common strategy is to suspend a tarp or other fabric (old sail cloth works well) by its four corners with a thru-hull fitting in the center connected to a hose and container.

Cost: $200 / 10 000 gallons If you scaled that production up to the 500ft2 area of your mainsail, you would receive close to 320 gallons of water. Of course, sails are not horizontal and as such their efficiency for water collection is reduced. But with rain often comes wind, causing the rain to travel at an angle to the ground, in which case the sails can be used to great advantage. Erecting a tarp or the other container such that it will catch water running off the sails is an efficient way to catch rain.

Emergency Measures for making water

Emergency Measures for making water

Solar Stills

During the Second World War, the US army developed spheroid solar stills for pilots or mariners that were forced down at sea. Stephen Callahan, of 76 Days Adrift fame, stayed alive by using a similar design that was packed into his life raft. Nowadays the most common form of inflatable solar stills is produced by Aquamate. The still is inflated and partially filled with salt water. Heat from the sun evaporates the water which condenses on the inside of the clear cover. The water then runs down the inside cover to a reservoir channel around the perimeter of the still. Production on a good day varies from 0.5-2 liters and they cost around $200-300 USD. To produce 10 000 gallons of water would take between 55 and 220 years. Cost: Irrelevant (output too low for regular usage)

Stove Top Still

A quicker method of distilling sea water is to use your gas range. There are many versions of stove-top ‘stills, but the fundamental concept is the same as the solar still, only boiling the water makes it much quicker. The cost of this method is similar to boiling fresh water; as seawater is only 3.5% saline, you could theoretically produce 0.965 of a gallon of fresh water for every gallon of seawater. However it is extremely cumbersome and somewhat dangerous to erect a still on a galley stove at sea. Cost: Irrelevant (too dangerous)

Hand pumps

Another emergency option is a hand-operated reverse osmosis pump. These pumps cost between $1000-2000 USD depending on the model’s output. Typically they produce between a pint and a quart of fresh water per hour of pumping. If you pumped four hours per day, it would take between 27 and 55 years to produce 10 000 gallons. Cost: Irrelevant (output too low)

Water under the bridge

A modern reverse osmosis watermaker is not for everybody and doesn’t have to be considered essential gear for a cruising boat. Sailors found water before the advent of high-output RO watermakers and those methods haven’t changed. Finding the system that works for you will depend on a variety of factors, not the least of which are comfort and budget. Whether it’s collecting rain in a tarp or filling jugs on the dock, rest assured, water is never far away as long as you know how to find it.

Robin was born and raised in the Canadian North. His first memory of travel on water was by dogsled across a frozen lake. After studying environmental science and engineering he moved to Vancouver aboard a 35’ sailboat with his partner, Fiona, with the idea to fix up the boat and sail around the world. He has written for several sailing publications including SAIL, Cruising World, and was previously a contributing editor at Good Old Boat.