Many sailors don’t realize that sailboat fishing is really quite simple and can be a sustainable (and delicious!) way to supplement their diets.

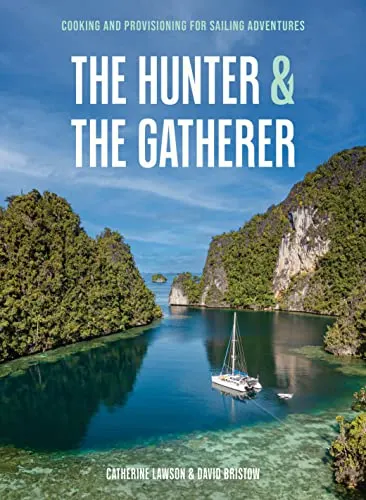

This article explains how to fish from your sailboat (and dingy) and is an edited extract from The Hunter & The Gatherer, a cookbook and provisioning guide by Catherine Lawson and David Bristow.

Catherine and David are long-time, liveaboard sailors and are currently cruising with their 10-year-old daughter on their 40ft cat, Wild One.

If the idea of harvesting your own seafood appeals to you, we recommend checking out their book The Hunter & The Gatherer, published by Exploring Eden Media. For every copy sold, one tree is planted! Check it out or order your copy here.

If you needed any more motivation to give sailboat fishing a try, Catherine and David have included a kickass recipe for Fijian Queenfish Kokoda (a conconut, lime, and chile infused ceviche) at the end of this post.

Waterborne is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Fishing from the back of your sailboat or yacht

Our boat Wild One really pulls its weight when we sail, and it’s a rare (or rough) day on the water when we don’t have at least one hand line out.

We regularly (fingers crossed) catch all kinds of tuna and mackerel, giant trevally, and maybe a mahi mahi (dolphinfish or dorado) or a wahoo this way.

I tend to keep the lines out longer than Catherine, but as long as we wind them in before sunset, we can usually avoid snaring sharks and the delicate mission of getting them off the line without harm.

Fishing tackle and equipment

On long, leisurely sails, we’ll often detour across sandy shoals or pinnacles where large pelagics (and the seabirds that give them away) tend to hunt.

We use large hand lines secured to the stern rails with bungy loops to take the shock load when a large pelagic bites down. Ours are wrapped with overpowered 350-500 pound mono to prevent big fish from snapping the lines.

I add a heavy-duty swivel, and trolling lures are crimped on for strength and to make the system more streamlined. I never tie knots, and we rarely lose a fish and never a lure (although they do get retired after too many bites).

My favorite lures are Halco’s deep diving, red-and-white ‘Qantas’ lures, but when big pelagics are around, I swap the standard treble hooks out for large singles.

There are a few reasons I choose hand lines over boat rods.

1. Hand lines are dirt cheap and available everywhere (we often beach comb them off the high tide mark).

2. They have no moving parts to break and are very quick to wind in when retrieving a catch, although you do need a bit of strength to wrangle in big fish.

Being on a catamaran, we can run out two lines without them fouling each other. But we do run them at different distances (one 25 meters, the other 40 meters) and with lures that swim at different depths.

Catching fish by boat is by no means a certainty, but it increases our chances of reaching an anchorage with protein ready to cook.

Dispatching your fish

I can’t stress enough how important it is to kill your catch swiftly and humanely, even when underway.

If the sailing conditions become too hectic to deal with a potential catch, I feel it’s better to pull the lines in rather than catch a fish that I can’t treat properly and respectfully.

There are lots of ways to bring large pelagics on board when underway, but here’s what I do aboard Wild One.

Once gaffed and safely on board, dispatch your catch humanely and swiftly by spiking its brain.

The brain is located in the middle of the fish’s head, just behind the eye, and you will know when you’ve hit it because your fish will spasm briefly, its fins will flare for a moment, and then the fish will then go limp.

Cleaning and fileting

To bleed the fish, lay it flat and cut behind the gills with your knife facing toward the fish’s head.

Slice from top to bottom until you see blood flow, then repeat on the other side.

Submerge or rinse the fish well in salt water, or if conditions permit, drag it by its tail for a minute or two to flush and clean it ready for filleting.

Slice off your fillets (don’t wet the fish again if you can help it), and place them in a large colander over a bowl (covered with a beeswax wrap or similar) to drain and rest in the fridge.

This resting helps drain the lactic acid that builds up in large, fighting pelagic fish. I usually drain fillets overnight, and whatever doesn’t get eaten while it’s fresh is bagged, labeled, and frozen.

Some sailors abhor the idea of sending fresh fish to the freezer, but when we’re cruising, especially in remote sailing grounds, fish provide an essential source of protein, and nothing is wasted.

Those species that are prolific and sustainably caught, prepared with respect, and fully utilized to reduce wastage, can help to feed you and your family when stores are a distant memory, and on all those days when the fish aren’t biting.

Shore Fishing

Boat life can get busy, but when I do have some downtime, you’ll find me holding the end of a rod while nursing something cold at day’s end.

When we jump into the dinghy to explore a new anchorage or to head ashore, I’ll always run a few lines out in the hope of snaring a fish before we hit the beach. If we have to use our fuel, we may as well turn every dinghy run into a fishing expedition.

When trolling in the tender along reefs, sand troughs, or mangrove-fringed shorelines, I use a scaled-down version of the hand reels on board or cast an overhead bait caster rod with smaller hard body lures or soft plastics.

This rod combo is extremely accurate when trying to land a lure into a tight location, or when chasing those ever-elusive barramundis, mangrove jack, and delicious varieties of cod.

These fighters demand patience and are all excellent eating, but if things don’t go your way, the mangroves are also great places to gather a feed of oysters at low tide.

In northern Australia, queenfish and trevally are regularly caught while dinghy trolling over sandbars, off river mouths, over inshore reefs, and sometimes by rod while standing on a beach with a beer.

Spearing reef fish

We spend a lot of time cruising in the tropics where coral reefs, and the trout, snapper, jobfish, and trevally they nurture, are generally abundant.

Anytime we can get in the water is an adventure, and while we are exploring a new reef, spearfishing provides a selective way to get dinner on board.

With a long enough breath-hold and plenty of patience, spearfishing can provide us with a meal in a manner that’s sustainable and respectful to the reefs.

This is really what got me into spearfishing because I can consciously choose a fish that is of suitable size and abundant in the places we drop anchor without harming any other fish in the process.

It’s also a great skill to learn, provides an excellent workout, and is one of the most authentic ways to take a fish.

I use a Rob Allen 1200 Sniper rail gun with dual bands and a 7mm carbon steel shaft. I find that the shaft stays true and is more accurate than other guns I’ve owned.

EDITOR’s Note: Some reef fish contain a toxin that causes a food-borne illness known as Ciguatera. It causes gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms and in very rare cases can be fatal. For this reason, many cruisers avoid eating reef fish altogether.

When you have to buy fish

Sometimes the fish just aren’t biting, and the reef fish are too skittish and too small to be speared. When we face a dry spell, we revert to our vegetarian ways, tucking into tempeh, beans, eggs, and lentils.

There’s always the option of buying fish as we go, from passing fishermen who visit our anchorages or in local markets where the daily catch comes with few food miles.

But bigger centers and supermarkets challenge conscious consumers who want to know just how sustainable their dinner really is. It can be difficult (and sometimes impossible) to know where and how a fish has been caught and whether a particular species is abundant in the location where it was taken.

These questions matter. 85% of global fish stocks are fully or over-exploited, depleted, or in recovery from exploitation. Thanks to our collective, growing hunger for seafood, all ocean ecosystems, including by-catch populations, are in peril.

The bulk of the guilt can be levied at large-scale fishing operations – trawlers, longliners, and gillnetters. But even at local levels, the stripping of coral reefs and continuing use of dynamite (blast) fishing has a devastating, irreversible impact.

When a blast went off in eastern Indonesia’s Kei Islands in late 2022, we thought our rigging had snapped and the mast was coming down.

We rushed out on deck, puzzled and perplexed, only to see a boatload of fishermen working with hand nets to scoop up fish. This desperate means to a meal is short-sighted at best, and the heartbreaking destruction of the reef and its minute and complex ecosystems will haunt these island populations for decades to come.

Fish farms or ‘sea ranches’ don’t always provide a better alternative and can be incredibly wasteful. Take, for example, Australia’s southern bluefin tuna.

This critically endangered species is caught from the wild and fattened in feedlots off the South Australian coast, primarily for export to foreign markets.

The Australian Marine Conservation Society (AMCS) reports that it takes up to 12 kilograms of wild-caught fish to grow one kilogram of southern bluefin tuna.

The maths just doesn’t add up, and wild-caught fish stocks used as tuna food are jeopardized further by the release of pollution from aquaculture farms back into the sea via uneaten fishmeal, antibiotics, and concentrated fish waste.

The good news is that you can wade through the confusion by downloading the Sustainable Seafood Guide app or check your choices at goodfish.org.au. In the USA, download the Seafood Watch Consumer Guide for a list of best buys wherever you live.

Recipe from The Hunter & The Gatherer

Queenfish Kokoda

Love it or hate it, raw fish gets a lot of people excited. When you land a beautiful fish (and it doesn’t have to be tuna), or someone gifts you a couple of fresh fillets after a day at sea, ceviche is a tasty, no-fuss way to get any meal started.

This Fijian-style ceviche, known as kokoda, balances out the raw fish perfectly and packs it with flavor.

To add crunch (and stretch the dish), stir through chopped tomato, cucumber, and fresh capsicum before serving, and dish it up in coconut shells, clams or, lettuce cups. Otherwise, savor it in its virgin state, slowly.

Ingredients

- 500g (1lb) queenfish (or any firm white fish)

- 2-3 limes

- 1/4 tsp sea salt

- 2 finely chopped spring onions (scallion)(or 1/2 red onion or 4-5 shallots)

- 1/3 cup finely chopped coriander (cilantro) and mint

- 1 fresh red chili, finely chopped(or 1 tsp dried crushed chili)

- 1/3 cup coconut milk

- cracked black pepper

- extra fresh coriander sprigs to serve

- Optional: add 1 roughly chopped tomato, 1 small cucumber (diced), and ½ small capsicum (bell pepper), chopped

Instructions

- Trim and rinse the fish, pat dry, and cut into small cubes.

- Place in a mixing bowl and squeeze over 1 ½ limes.

- Season with salt, and toss to combine.

- Refrigerate for 2-3 hours until the fish turns opaque.

- When ready to eat, drain the fish, add the spring onion, chopped herbs, chilli, coconut milk, a generous pinch of black pepper, and any extra vegetables, and stir well.

- Serve with lime wedges and extra coriander sprigs.

Notes

Safety note: Citrus juice does not kill bacteria or parasites that may be in the fish. Always choose either commercially-frozen fish or high-quality sushi-grade fresh fish for ceviche. Avoid cod, swordfish, monkfish, and all freshwater fish as they are highly parasitic. When in doubt ask an experienced local angler or fisherman.