Sailboats, unlike cars, don’t have the luxury of pulling over to the side of the road, whenever the driver needs a break. Fortunately, they can heave to, a simple technique for stopping a sailboat that is far more comfortable and controlled than just dropping the sails and drifting.

Over three years and 13,000 miles of blue water sailing, we hove to on many occasions. By adjusting the mainsail, headsail, and rudder, we were able to comfortably stall our boat for hours, even days, at a time. It’s a simple maneuver that we’ve found useful in many different situations—stopping the sailboat to make repairs, take a swim, or wait for daylight to enter a harbor.

Notes: this post contains some affiliate links. If you purchase through these links we’ll earn a small commission

Heave to definition and meaning

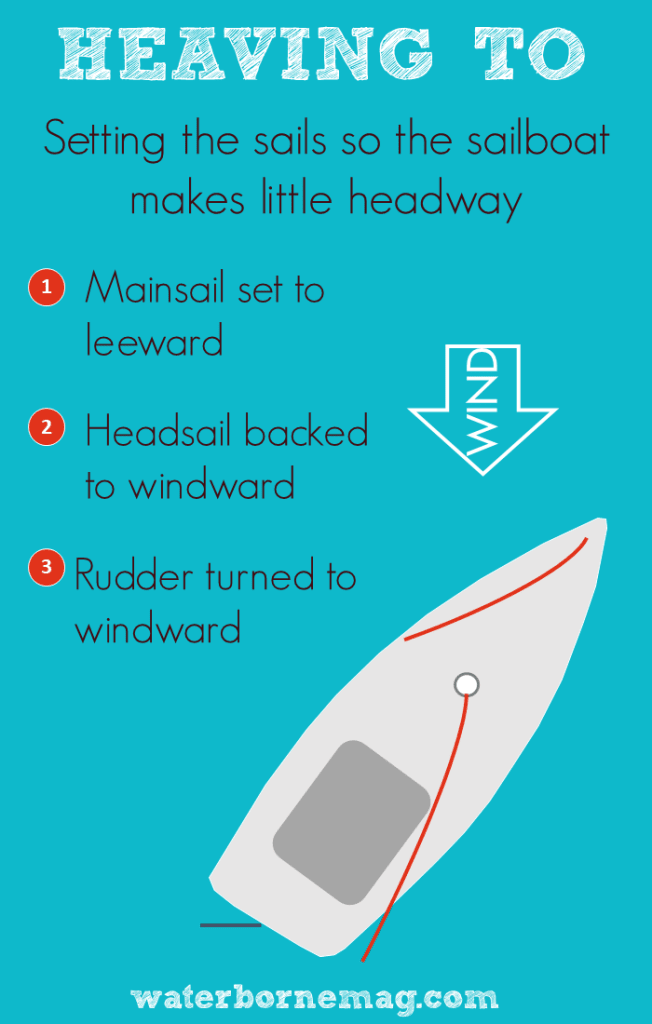

The 67th edition of Chapman Piloting & Seamanship defines heaving-to as “setting the sails so that a boat makes little headway, usually in a storm or a waiting situation.”

I would add that it’s a very useful technique in everyday sailing (e.g., making repairs, breaking for lunch), especially for short-handed and solo sailors.

How does it work?

Heaving to is accomplished by backing the headsail (i.e., sheeting it to the windward side). This counteracts the force of the main sail. The headsail pulls the bow to leeward, while the mainsail pushes the bow back to windward. This push and pull between the sails results in halting the boat’s forward progress.

Benefits of heaving-to

Stops forward progress

Heaving too is a controlled and comfortable way of staying relatively stationary.

Makes the boat more stable and comfortable

By staying at 40-50 degrees to the wind, with the bow taking the brunt of the waves, the boat becomes more stable.

Some also say that as the boat drifts downwind, the keel creates a slick of disturbed water which further dampens the effect of any breaking waves to windward.

Offers a quick getaway

If you need to move in a hurry, say to get out of the way of oncoming traffic, your sails are already up and ready to propel you forward. You can be back underway within seconds.

When to heave to

Here are some situations where you might find heaving to useful:

- Waiting for another boat. On a 26-day Pacific crossing, we hove to in order to wait for a disabled yacht so that we could accompany them for the rest of the passage.

- Waiting for daylight. Rather than risk entering a harbor with unknown hazards, we would often heave to and wait for daybreak.

- Freeing up hands from the helm. Heaving to is a helpful technique for short-handed or solo sailors who don’t have a self-steering wind vane or autopilot. While hove to, the person at the helm is freed up to do other tasks.

- Making repairs en route. We hove to when we needed to make repairs to our auto-pilot while during a multi-day passage. It was also helpful when we needed to stop so we could dive and inspect our rudder for damage.

- Having a coffee break or making lunch. Sometimes it’s just nice to take a break. The stability that comes with heaving to can make cooking a meal below decks a lot easier.

- Going for a swim. On hot days near the equator, we’d heave to and indulge in a quick dip (while tied in of course).

- Letting seasick crew rest. If your crew is struggling with seasickness, heaving to may offer them some respite.

- Heavy weather. While we’ve fortunately never needed to heave to on account of bad weather, we know sailors who have. One friend spent three days hove-to off in heavy seas and strong winds off the coast of Australia.

While heaving to can be very effective in heavy sea states, it’s important to recognize that there is no single storm tactic that is always going to be the right choice, regardless of the boat and conditions. In truly extreme weather, say a survival storm, you may also need to consider the use of a sea anchor, drogue, and more advanced techniques. For more on storm tactics, Storm Tactics: Modern Methods of Heaving-to for Survival in Extreme Conditions by Lin and Larry Pardey.

Can all sailboats heave to?

Some say that modern boats with fin keels don’t heave to as well as a full keel boat, but you should be able to heave to on most sailboats, including catamarans.

It is possible to inadvertently end up fore reaching while attempting to heave to, which may account for some confusion over whether your boat is properly hove to or not. We discuss forereaching in more detail at the end of this post.

How to heave to

The goal of heaving to is to balance the mainsail and a back-winded headsail so that they cancel each other out. When done properly, the boat stays at roughly a 40-50 degree angle to the wind and waves while making minimal headway.

Finding that balance is different on each boat. Your boat’s sail plan, displacement, keel type, and hull design will all affect how she heaves to. While most sources recommend aiming for 40-50 degree angle to the wind, there are boat types that might heave to anywhere from 30-60 degrees off the wind.

You’ll need to experiment with how you set your sails on your own boat to achieve the right combination.

As with any new skill, practice in good weather when the conditions are steady and well within your comfort zone.

1. Reef according to the conditions.

If you’re at full sail, your first step may be to reef both the headsail and mainsail appropriately for the conditions you’re sailing in. On our boat, this would have been full sail at 5 knots of wind and fully reefed at 25 knots.

Too much sail and you’ll risk being knocked down, too little sail and you won’t stay pointed in the right direction.

To reef the headsail this may mean furling your genoa, using a staysail, or even getting out your storm jib. In some cases, you may want to swap out your reefed mainsail for a trysail.

2. Sail close haul.

Sail close haul, ensuring your sails are tightly trimmed.

3. Slowly tack the boat without releasing the jib.

You should land on the new tack with a backed jib.

4. Steer the boat so it stays at a 40-50 degrees angle to the wind.

The backed headsail will cause the boat to head down past 60 degrees. Steer to compensate for this and keep the boat 40-50 degrees off the wind.

Feather the main as you work the boat back upwind. Take care if you approach 40 degrees – too much momentum will cause you to tack back again.

If the boat won’t round up, your headsail is overpowering your mainsail. You may need to reduce the head sail area to find the right balance.

If the boat wants to round up into wind and tack, your mainsail is overpowered. You could try easing the main slightly.

5. Turn the rudder to windward

Once you’re reached 40-50 degrees and you’ve bled off speed, turn the rudder all the way to windward (wheel to windward, tiller to leeward) and lock it off or lash it in place.

Watch to see what your boat does and if it stays in a relatively stable position, within 40 to 50 degrees. Don’t stress if the boat swings between 40 and 50 degrees. This is normal and is caused by the wind and waves. The boat should stay hove-to unless thrown off by a big wave or gust.

Getting out of heave to

When ready to get underway again, bring the rudder amidship and release the windward sheet, allowing the jib to flip to the other side. Trim your jib on the leeward side and once you’ve got some forward momentum you can head on your intended course.

Other tips for heaving to

Stay aware of your speed and course, and always maintain a good lookout. Though not underway, you can still drift into hazards or get into a collision. It’s a good idea to give yourself enough sea room (space) when heaving to.

If you’re in a busy area, heave to on a starboard tack (keep boom on the port side) to maintain the right of way over sailboats on a port tack.

Inspect your sails for chafe. When heaving to, your jib sheet or the clew of your genoa may sit and rub on the shrouds. If left unattended it will eventually wear through your sheet or sail.

You can prevent this by reefing the genoa, putting chaffing protection on the shrouds TK, or even re-running the sheet inside or between the shrouds.

Watch Skip Novak demonstrate how to heave to in this video

Fore reaching vs. heaving to

Fore reaching is an alternative to heaving-to in some situations. Unlike heaving-to which completely stalls the boat, leaving you drifting at 1-2 knots downwind, fore-reaching keeps a boat moving forward at 1-2 knots to windward.

It may involve sheeting the jib amidship (not backed) or lowering it entirely while keeping a reefed mainsail sheeted in tight and the helm kept slightly to leeward.

Fore reaching can be a useful technique when you want to continue to make headway but go much more slowly. Say, for instance, if you were heading into an outgoing tide of current but wanted to maintain your position.

Some think that fin-keeled boats are prone to unintentionally forereaching while attempting to heave-to. Unlike heaving-to, fore reaching does not provide the slick of calmed water on the windward side of the boat.

Heave to or hove to?

Heave to is a phrasal verb. In the present tense, you might say, “Let’s heave to and take a break for lunch.”

If the action is complete (past tense), you can use the past participle: hove to. For example, “The sailing ship hove-to for days off the coast of New Zealand.”

Fiona McGlynn is an award-winning boating writer who created Waterborne as a place to learn about living aboard and traveling the world by sailboat. She has written for boating magazines including BoatUS, SAIL, Cruising World, and Good Old Boat. She’s also a contributing editor at Good Old Boat and BoatUS Magazine. In 2017, Fiona and her husband completed a 3-year, 13,000-mile voyage from Vancouver to Mexico to Australia on their 35-foot sailboat.