Guest poster, Brian Gartland and his eight and nine-year-old, Buddy and Scarlet, spend winters living aboard, cruising the Abaco Islands in the Bahamas. For Brian, teaching his kids to be brave and love the ocean meant addressing a few fears of his own.

Growing up brave – “Why I let my kids play with an apex predator”

On Moonshine, our 36’ PDQ catamaran, we worked our way up close to the shore of Manjack Cay in the Abacos, where there was a sand hole in the Turtle Grass with good holding. When I got the anchor set and walked back to the cockpit, Buddy and Scarlet, my seven and eight-year-olds, were waiting on the stern steps with their masks and snorkels. As soon as I shut off the engines, I gave them the word and they flopped overboard.

Down the companionway I went, to retrieve a cold beer, and when I stepped back on deck, I noticed a large, dark, shape, moving toward the kids, along the bottom. I got to the stern rail just as it passed under Buddy. His head popped out of the water and, spitting out his snorkel, he yelled, “Dad, a shark!” Then he stuck his face back in the water and swam off after it. I grinned and opened my beer. “Good job, Buddy!” I shouted and started wondering what to cook for dinner.

“When I stepped back on deck, I noticed a large, dark, shape, moving toward the kids, along the bottom.”

On the beach, at a bonfire, cruisers were telling each other scary shark stories. I kept my mouth shut and watched Scarlet listen to the adults until she couldn’t take any more. She broke into the conversation and said, “Why are you afraid? They don’t eat people.” There was silence at the admonishment from an eight-year-old, and then the group broke into laughter and moved on to something else. “Good job, sweetie,” I whispered to her. “Can I have another marshmallow?” she asked.

After another day in the anchorage, as the sun began its fall toward Little Abaco, I waited in the cockpit for the kids to drag themselves, exhausted, up the stern steps. They had been diving to the bottom and grabbing sand and Turtle Grass to line the hermit crab habitat that they made out of an old refrigerator drawer they found washed up on the beach.

“Are you two done swimming? Can I clean the fish now?”

“We’re done,” Scarlet replied.

“Can we see if Peaches is around?” Buddy asked.

“Sure,” I said, pulling the Hogfish I had shot that day out of the cooler and setting it on the fish cleaning station.

After I got the filets off and rinsed them, I threaded an old dock line through the hole that my spear had made in the carcass, dropped it overboard and tied the other end to the stern cleat. “It’s in the water,” I yelled to the kids, who came out and sat on the stern to watch. In the galley, I barely had time to bread the filets before I heard, “There she is!” and scrambled up to the cockpit. “Where?” I asked, sticking my polarized sunglasses on my face. Buddy pointed straight down as Peaches, our local Tiger Shark, slowly swam out from underneath the boat, bumping the Hogfish carcass with her snout as she passed by. My breath caught at her size, though we’d seen her many times before. She was easily longer than our twelve-foot dinghy.

When she turned to come back, I grabbed the line with the Hogfish on it and waited. She took it in her mouth, and when I felt her start to pull on the line, I gently pulled back, slowly turning the thousand-pound fish up from the bottom. When her head broke the surface, she closed her eye and rolled over, showing us the stripes on her flanks and her white belly. I pulled her up a couple more times before she tired of the game and severed the line with a quick jerk that made the rigging shudder.

“Do we have another fish?” Buddy asked as we watched Peaches swim figure eights, searching the bottom.

“That’s the only one I shot today,” I replied, thinking about putting on my mask and fins and getting in the water with Peaches.

The idea of it gave me chills. I wondered if that twinge of fear that shortened my breath came from my lifelong exposure to negative images of sharks, or my fear of orphaning my children. I wondered if I was brave enough to put my money where my mouth was and prove to Buddy and Scarlet that humans are not food for sharks. I looked at my kids, intently leaning out over the water, hoping Peaches would make another pass, and I knew that they would get in with her in a flat second if I told them they could. They had no fear because I never taught them that sharks are scary.

In all likelihood, it would be fine, I told myself. Sharks don’t eat people. Scarlet and Buddy had been splashing around behind the boat for hours. Peaches showed up almost immediately after I put the Hogfish in the water. Surely she had seen the kids swimming. Surely, with her superior underwater senses, she had known they were there. If she had wanted to eat Scarlet and Buddy, she could have done a quick job of it.

“Letting my kids in the water with an apex predator, seemed like an utterly insane idea”

Letting my kids in the water with an apex predator, seemed like an utterly insane idea; at least until I considered how many parents put their children in an automobile every day. By a long shot, the leading cause of accidental death among children is traffic accidents. We don’t think twice about strapping our kids into those statistical death machines, yet people are terrified of sharks, despite the fact that almost no one gets killed by them. Only four or five people in any given year, worldwide. It’s not the potential for catastrophe that makes us afraid, I realized, it’s the novelty of the danger. What we’re used to feels safe.

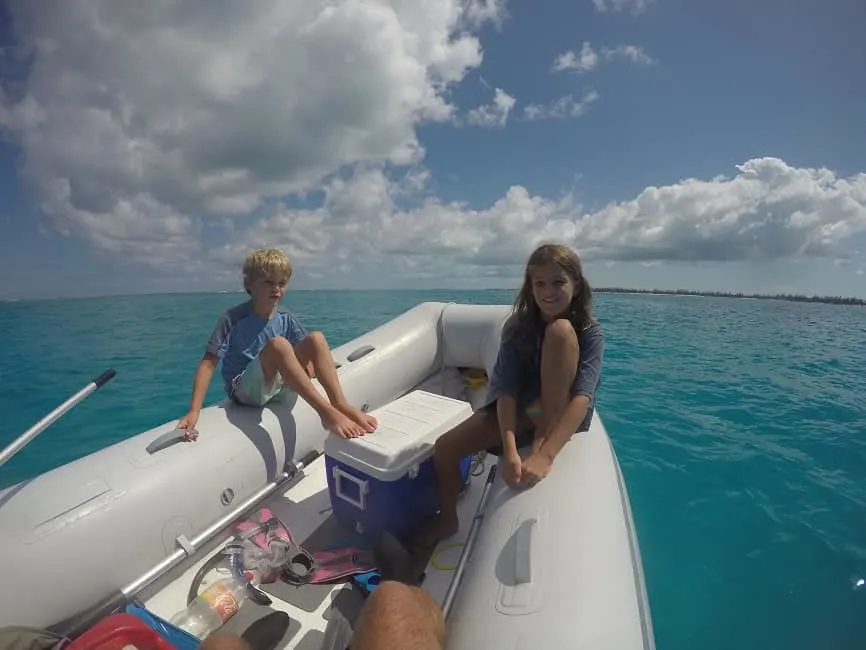

On our last dive day of the season, the Sea of Abaco was so calm that the surface was like a glass lens. The kids leaned over the sides of the dinghy, watching the bottom, as we ripped along at twenty knots, calling out the Sea Stars, Rays and Conch that they could see, despite our speed. The narrow pass between Crab and Fiddle Cays had not a ripple, at slack tide, and we could see to the bottom of the thirty-foot hole in the middle of it. The reef was a stunning array of electric blue and I was giddy with excitement. The visibility was the kind that makes you feel like you’re flying rather than floating.

I turned north once we were on the reef side, weaving around and between the scattered coral heads that, after ten winters, I had learned to recognize individually, even from the surface. When the dinghy coasted to a stop at the edge of the sand ring that surrounded one of my favorites, I tossed the anchor and watched the line pile up on top of it. There was zero wind and zero current. Perfect conditions for the kids. “This is going to be really good, guys,” I said.

As soon as we swam up to the coral, the kids both started talking to me, unintelligibly, through their snorkels, excitedly pointing out the fish they could identify, among the hundreds that were swimming in and out of holes in the coral. I knew they would be perusing the reef identification books and adding to their lists when we got back to Moonshine.

There was huge ray buried in the sand for its daytime nap, only its eyes and tail visible, and I dove to the bottom and gave it a gentle poke with my spear so the kids could watch it explode out of the sand. There were schools of Gray Snapper and Grunts, Squirrelfish and Sergeant Majors, Porgies, Vermillion Snapper, Bermuda Chubs. Scarlet pointed out a Hogfish and shouted into her snorkel but I didn’t want to bloody the water with my kids in it.

“I heard the unmistakable sound of both kids shouting “Shark!” into their snorkels. When I looked up, I saw the barrel shape of a large bull shark swimming slowly toward us.”

Halfway around the coral head, there was a cave where I had speared big grouper before. I couldn’t resist diving to take a look, and just as I peeked in, I heard the unmistakable sound of both kids shouting “Shark!” into their snorkels. When I looked up, I saw the barrel shape of a large bull shark swimming slowly toward us, along the bottom, thirty yards away. With a few kicks of my fins I surfaced between my kids and blew my snorkel. The bull rose toward us in the water but turned when it was ten yards away. I estimated that it was between eight and ten feet, a very big fish.

We held our ground and watched it swim off, Scarlet and Buddy oohing and ahhing into their snorkels. I took deep breaths to slow my racing heart. When the shark was out of sight, I took my children’s hands and swam us back toward the dinghy, proud that I had been the only one afraid of the enormous fish.

“That was awesome!” Buddy said after I boosted him over the gunwale, into the dinghy.

“What kind was it, daddy?” Scarlet asked as she came over the other side.

“That was your first bull shark, guys.”

“Cool!”

When we were done with our last dive that day, I pulled up the anchor but didn’t start the motor, letting us drift with the tide and watching the sun get lower over the island. I remembered the first time I got in the water off Manjack, ten years before, and the awe I felt at witnessing the teeming alien world that was just under the surface. Abby, Scarlet and Buddy’s mom, had been pregnant with Scarlet then. I had a deep desire to show my unborn baby the beauty of a healthy coral reef, along with a fear that it would all be gone by the time my children were old enough.

We lost Abby when the kids were five and six, to cancer. I knew then, that they would have to be brave, and when I looked at them, perched on either gunwale, soaking wet and exhausted, I was intensely proud. I knew, that if my brave kids had courage enough to swim with sharks, if they could decide for themselves what to fear and what not to, they would have the courage to calmly confront any of the other monsters, real or imagined, that fate might cast in front of them.